Title: Lost Tapes Vol. 7 Menghino Saulle, Filippo Pellicani e Franco Sette

Groups: Mimì Laganara e la sua orchestra, Gianni Quin Jolly, Sette e i magnifici

Years: 1952/1989 © 2021

Graphic: Giulio Lekklub

English translator: Rosangela Iovino

Discover, digitalization, sound track selection, editing: Livio Minafra

Mastering and restoration sound engineer: Gianluca Caterina

Label: Angapp Music – It

Produced by: Livio Minafra

Financed by: Pino Minafra

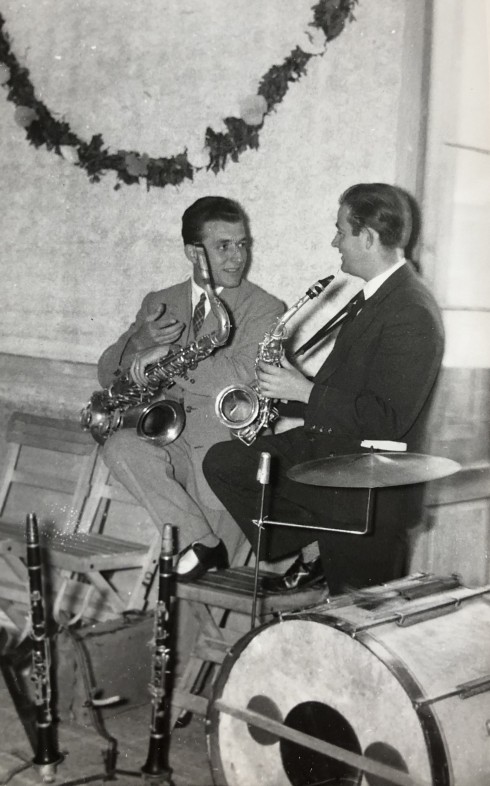

Three disciples of the Banda, of the Music School in Ruvo di Puglia and Maestro Antonio Amenduni. Three friends. Three buddies. Three musicians bewitched by pop music and post-war jazz.

Mimì Saulle, alla condusciòn dus mèri

Domenico Saulle, known as Mimì or Menghino, was born in Ruvo di Puglia on January 3, 1917. He was encouraged to pursue solfeggio and trumpet studies by Maestro Antonio Amenduni, then Municipal Master of the Ruvo di Puglia School of Music. After school he flanked his father as a coppersmith, the ancient profession involved in building and repairing zinc and copper pots (“caldare” in dialect). The Music School and therefore the Banda were mostly made up of “children of the people”. In ’43, the postwar period enthusiasm and the reconstruction prompted him to focus on music; he thus took a remarkable tour of weddings and parties, collaborating with many local ensembles, often together with the saxophonists from Ruvo as Franco Sette, Nunzio Iurilli and Filippo Pellicani. He was famous in the village for his sound that, like a blade, stood out above the Holy Week of Ruvo di Puglia. Particularly in processions, especially in the nocturnal procession of the Eight Saints’ statuary complex (Otto Santi). At the same time, he was an entertainer, a macchietta, who played the trumpet even with only the mouthpiece. One of his famous catchphrases was: “Alla condusciòn dus mèri”! And when someone asked him the meaning, he answered: “Stat cit, sacce tut eje”, that means: Shut up. I know! He knew how to pass from the Banda’s seriousness to pop music and even to jazz repertoire improvisations. It is no coincidence that the only sound testimony of his sound today is due to the Orchestra of Mimì Laganara, the subject of the cd Lost Tapes vol. 4, in which we also listen to Saulle. Destiny wanted that in 1952, a friend of Mimì Laganara’s, a certain Peppino Valls, wanted to test a philophone during their rehearsals, so today we find precious sound documents that testify for yesteryear, and above all, the talents, among others, of Lorusso on alto sax, Saulle on trumpet and Pellicani on tenor sax. So here is Saulle, with his sound, as a soloist in Caravan, Bahia and Moonlight Serenade and as an improviser in pieces Negri a Zonzo and 32 Battute in Fa. He played in about 250 weddings/balls a year in his life. He collaborated with Nilla Pizzi, Jula de Palma, Pino Rucher and many others, although always remaining in Puglia. At the end of the 1960s, he went through intense exhaustion – he worked day and night to support his large family of 10 children – a situation that forced him to change his life, accepting a job as janitor. He died in Ruvo di Puglia on November 27, 2002.

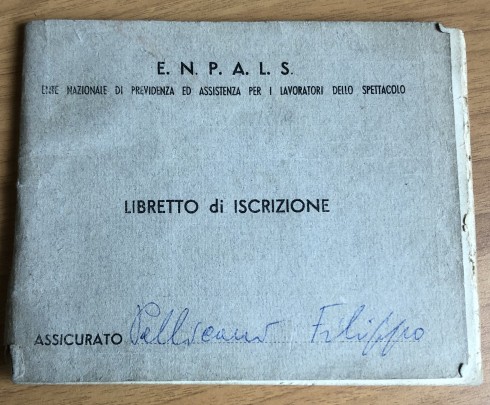

Filippo Pellicani: the White Coleman Hawkins

Filippo Pellicani is also another disciple of the Banda. He was born in Ruvo di Puglia in November 1923. Still, he was declared in the registry office on January 1, 1924, a practice then widespread to prevent children from finding themselves in school classes as the youngest. He was soon enrolled in the Music School where he studied solfège and clarinet, making quickly his debut in the Banda. For the occasion, Maestro Amenduni went to the family home to ask and buy long pants, because the child would “join the Banda for the first time” in a few days. At the time, all children wore shorts all year round. Filippo expanded his knowledge to pop music and jazz by moving to the sax in the immediate postwar period, just like his friends Enzo Lorusso, Santino Tedone, Nunzio Iurilli, Franco Sette, etc. On the other hand, pop music made it possible to earn money through weddings and parties and liberate moments of improvisation and interpretation of American jazz songs. Pellicani was attracted by the tenor sax sound of Coleman Hawkins, the last exponent of classical jazz, together with Lester Young (before Charlie Parker). He had many of his records. It is no coincidence that Pellicani’s tenor sax timbre was sinuous and dark almost as much as baritone sax. Bruno Giannini noticed this and, returning to Bari around 1948, from his tours in Milan and beyond (in the company of Gorni Kramer and Franco Cerri), he wanted him in his quartet alongside the great guitarist Pino Rucher and the drums of Vito Rutigliano “Ciù ciù” (uncle of the pianist Mirko Signorile). Giannini had already been touring American Bases in a quartet with the then very young Santino Tedone since ’43. In 1945 he moved to Milan. In the South, the war had already ended two years earlier. Giannini found himself musically ahead of his time, due to the V-Discs he listened to and the jams with American musicians. Gorni Kramer noticed it immediately and he wanted him for a few years, until the family claimed him in Bari, to continue the business in the family shop. It was a great pain for Giannini to give up his career. Just think that only ten years later, the same fate would have happened to Filippo Pellicani. But let’s go back to the early 1950s. Giannini integrates him into his excellent quartet. Pellicani plays in the area with many bands. Once again, we find him with Mimì Laganara in his splendid orchestra / big band born in Bisceglie, the object of the Lost Tapes vol. 4. Here he is as an orchestral and tenor sax soloist together with Mimì Saulle (trumpet) and especially Enzo Lorusso (alto sax and clarinet). Such is the case of Caravan, Negri a Zonzo, The Boogie Boo and 32 Battute in Fa. In those years, Pellicani also set up his orchestra. But then the improvement in quality. In 1954 or shortly after, Pellicani moved to Milan when Gianni Galavotti, aka Quin Jolly, called him. Until about ’62 he recorded disks and regularly lived on music, also touring Germany, Spain, Portugal and Lebanon. They were the most significant years for our musical life. In Milan, he played regularly at the “Gatto Verde club” and collaborated with Nilla Pizzi and the great Gorni Kramer and Armando Trovajoli. He was nicknamed the White Coleman Hawkins. There are also numerous recording sessions. In this sense, his collaborations with Quin Jolly himself stand out, which led him to record for Odeon, Parlophon, Smeraldo Records and to be distributed, with such recordings, in Spain and even in the United States. And this is the only other sound testament of those fruitful and happy years in Milan. Then here is the emotional solo of 1958 of Mambo Alfabetico and the other entertaining pieces of the Quin Jolly repertoire. Pellicani also appears on clarinet and of course tenor sax: Ohi Marì, When and Venus. In 1957, Trovajoli was founding the RAI Light Music Orchestra in Rome, for which he organized auditions. Pellicani thought about it, but then, as for Santino Di Rella, he preferred the free profession, recommending this competition to Santino Tedone. The fact is that Tedone won and until the 1980s he was permanently the first clarinet and second alto sax in Rai. One day, Pellicani returned to Puglia and, convinced and advised by his family, opted for a safe and permanent position in the Bank, relegating music to Saturdays and Sundays. “My father wept when he left his profession,” recalls Antonio Pellicani, Filippo’s son. Thus, there remains a prestigious quote from Adriano Mazzoletti in “Il Jazz in Italia/Dallo Swing agli anni ’60 (EDT)” or in English: The Jazz in Italy/from Swing to the 60’s” erroneously indicated as Pellicari, together with these recordings. Other times. and other stories. That’s the way it went for Pellicani too. Pipuccio – as he was called in the village – used to say when someone asked him what he played when he improvised: “It’s all I hear inside, from my heart and soul. Beyond the technique. Improvisation cannot be studied. That’s what you feel at the moment “. He died in Trani on August 31, 2004.

Mimì Laganara tells about Saulle and Pellicani:

When they joined my orchestra, these musicians from Ruvo di Puglia, whom I did not know and who were suggested to me by the pianist Tonino Minervini, in addition to their technique and their virtuosity, their characters also struck me. Mimì Saulle was whimsical, brilliant, ready for a sketch. When he got excited in solos, he would stand up on the chair and trumpeted here and there, even hinting at a few dance steps, at risk of falling! When he became a little confident, one day he asked me if he could have a bottle of wine to keep under the chair: he told me he needed it to moisten his lips … but I understood very well that he needed it to re-energize himself a bit. Of course, I immediately agreed to his request, and I have to say that, since then, his musical performances have greatly improved! When the song “Anema e Core” came out in 1952, after rehearsing it, he suggested a nice expedient: we would start playing it, intro and verse, in the meantime he would reach the gallery, up above, and once arrived the time for the chorus, he would play the tune in a perfect, melodic solo. It was a tremendous success; no one expected the sound of the trumpet to come from up there. He took everyone by surprise in flawless execution. If you like, he anticipated what would come much later: the stereo sound! I also remember there was no drum part then, so the drummer had to rely on his memory. Then Saulle made sure that his part was also read by the drummer because, as you undoubtedly know, the trumpet blasts were well marked with the proper accents, and therefore the drummer was able to read them and highlight the bars. He was a volcano! I remember of Pipuccio Pellicani instead that he was a serious, precise, conscientious musician who was meticulous in his performances. But when “his” moment came, he was lively, especially in the swing solos, while in the slow songs he was soft, confidential and sometimes sensual! One day he came to rehearsals with a sheet of paper on which musical notes were on a staff. The melody was marked in the treble clef with the chords written underneath: it was the famous piece “In a sentimental mood”, by Duke Ellington, which he also performed in solo on the clarinet. We tried it like that, on the imprint, and it turned out a stunning performance which Enzo Lorusso also joined, with the alto saxophone and of which today, fortunately, we have the recording (which can be listened to again in the cd Lost Tapes vol. 4 – Mimì Laganara, author’s note).

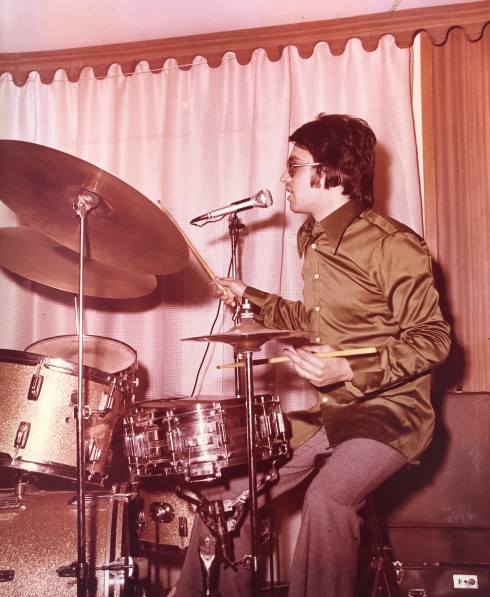

Franco Sette, a “quality barber”

Franco Sette was born in Ruvo di Puglia on March 18, 1925. He was soon enrolled in the local Music School, directed by Maestro Antonio Amenduni and his brother Alessandro. Those were the years when few had the radio, and the TV had not made its appearance yet. Franco Sette immediately revealed a formidable ear and was soon included in the staff of the Banda as a clarinettist. After the war, he opened a barbershop while his appearances in Banda gradually thinned out. To be fair, Sette embodied a particular category of musicians from Southern Italy, in other words that of barbers. As a matter of fact, there were the barbers playing mandolin or accordion, often self-taught, and the barber clarinettists or saxophonists, mostly coming from the bandas, like ours. Franco Sette was, in fact, active in many local bands. We find him on alto sax and clarinet initially with Nunzio Iurilli, Filippo Pellicani or Mimì Saulle in local groups such as the group “La Forgia” in Molfetta, the Ambra Orchestra in Bisceglie, always exquisitely for weddings and parties, both in the halls and in the houses, as was customary at the time. The repertoire was made up of all sorts of dances; pop music hits, polkas, cha cha cha, quadrilles, can can, slow, waltzes, twists, boogie-woogie, hully-gully but also American songs and rock’n roll. Later, he formed his own group that, over time, he called Sette e i Magnifici, not surprisingly inspired by the title of the 1960 western film directed by John Sturges. It can be said that the legend of Franco Sette begins here, for everyone in town “Cellùzz”. A Lilliputian story, however, as Cellùzz never left the region and was only famous within a radius of 40 km. In fact, between the 1950s and 1976, it can be said that almost all weddings and parties within a few kilometres saw him as the protagonist. Sometimes 30 performances a month. Sometimes more than one commitment a day. Few remember a beard made personally by Cellùzz because he was always around. They played for hours, without sparing themselves, often until late at night and never stopping. Antonio Montaruli, barber, shop neighbour, and his guitarist from 1966 to 1976, tells us that Sette “sometimes yes, sometimes not, he hinted at the key of the new piece. Almost always he played one piece after another, and you had to follow him by ear, understanding what song it was. I followed him while Pinuccio Di Gioia, the keyboard player, was always in trouble, looking for scores”.

Antonio Pellicani, son of Filippo Pellicani and one of Franco Sette’s drummers, tells us that in 1970 the famous saxophonist Fausto Papetti stayed at the Hotel Pineta in Ruvo di Puglia, busy for evenings on-site. Franco Sette was playing for a wedding and among other things, being aware of Papetti in the hotel, we do not know how much in homage and how much on a dare, he purposely went over some of Papetti’s successes, enriching them with small improvisations and distortions. In particular in a famous cheval de bataille by Papetti, Franco Sette took a very high note for the alto sax, in the finale. At a certain point, Papetti left the room and ,attracted by the sound of this sax, entered the hall to compliment Sette. Franco Sette, happily surprised, thanked him with a «Maestro…» as if he wanted to murmur words of reverence. Well, really! Papetti interrupted him by uttering « For heaven’s sake. You are the Master. Maybe you don’t realize, but you are a great saxophonist». Other details emerge from the memory of Montaruli himself. Papetti also asked him in which orchestra he played, but Sette replied that he played with his group, in the area, for weddings and soirees. Thanks to the talents just heard, Papetti thought that Sette was joking and asked him again which Italian group he worked in or which tours he was involved in. But Sette reiterated what he had said. A great friendship was born that lasted many years. Among other things, Papetti himself urged Sette several times to “cross” the Apulian borders, also proposing him to record companies, but Sette always wanted to stay in Puglia. This recording made in the early 1980s, with significant historical clarity, by Mr Rocco Di Modugno, is the only testimony of Sette’s sound. A very unfortunate recording since Nicola Di Gioia’s drums were not amplified (so much so that it was recreated in style in July 2020 by drummer Antonio Ninni). “Furthermore, during the whole concert, the music was “enriched” by a “talkative” lottery and “trying your luck man” as well as by an alarm from a Fiat parked nearby, which went off several times”. Fellini, Fantozzi or Peter Sellers in all respects! Low-fi tapes, furthermore , since they come from a VHS audio, which nevertheless allow us to enter an era. An era that, to the detriment of the early 80s, is revealing of pre-Beatles music as it lacks a singer, considering that from the Beatles onwards, namely the early 60s, the demand of musical groups was no longer linked to the sax or trumpet soloist, but to the singer and the electric guitar; in this way many, just to keep living, had to comply with by including a singer and learning to play the guitar. At the beginning of the 1980s, Franco Sette was practically no longer in fashion and had almost retired. The local PCI (Italian Communist Party) organization managed to convince him to play for the “Festa dell’Unità”, and Sette revisited his successes with his typical and above all old team, “old-fashioned” training, with the saxophone always the thematic protagonist. The recording reveals a repertoire of jazz: All of Me, Pennsylvania 6-5000, In the Mood, Caravan as well as the magnificent Stardust (present in two versions), as well as blues like Round Around the Clock, of cha cha cha like Ciliegi Rosa, of polkas, such as La Risata del Sassofono/The saxophone laughs, probably written by another barber from Ruvo, Marino Pellegrini, uncle of Enzo Lorusso and father of the first vibraphonist from Ruvo di Puglia, Mike Pellegrini. A dive into a sound and a still naive village world between the post-war reconstruction and the economic boom. A piece of black and white music. A tale that no longer exists, of extreme musical dignity, where barbers played between one beard and another, where people celebrated at home, where an ordinary person, holding a musical instrument, became someone, and where, above all, the songs still relied upon instruments such as saxes or clarinets and not yet solely on the singer’s voice. Franco Sette died in Ruvo di Puglia on 8 April 2009.

Livio Minafra, agosto 2021

English

English Italiano

Italiano